Upwell Researcher Derek Aoki describes the first time he saw a leatherback sea turtle crawling on to a beach to nest as “An awe-inspiring experience. I honestly did not believe a turtle could be that large.” For the past four years, Derek has been working towards his PhD in Integrative Biology at Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute with his advisor Annie Page and co advisors, including Upwell’s Dr. George Shillinger. He says he chose to focus his studies on leatherbacks because “They are so unique compared to the other six species of sea turtles, and one of the most threatened sea turtle species in the Atlantic Ocean.”

Derek spends nights between April and June patrolling Juno and Jupiter beaches in Southeast Florida. When he spots the hulking silhouette of a leatherback crawling up the beach, he springs into action to take advantage of this rare moment when a leatherback is easily accessible. Derek works as part of a collaborative team that collects data for multiple research projects in under 30 minutes by collecting body measurements, blood and skin samples, weighing a small subset of turtles, and more. Last summer, at the suggestion of Dr. George Shillinger, Derek began adding an acoustic tag in addition to a satellite tag on the leatherbacks carapace in order to test the tags viability as a tool for collecting long-term data on the turtles movements.

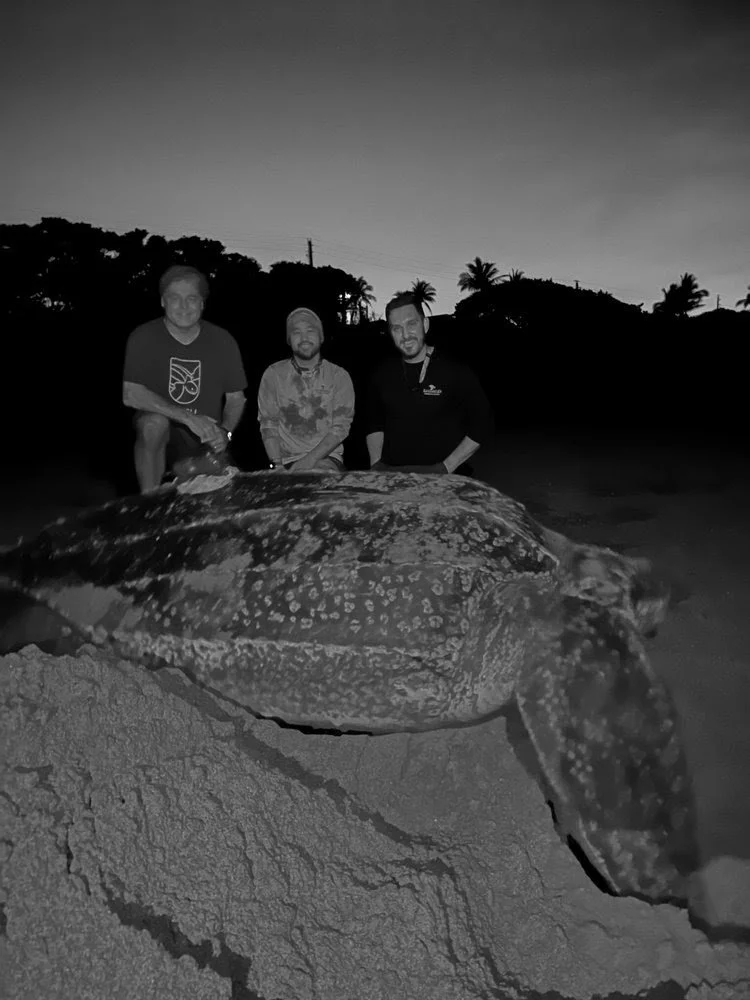

Photo by Derek Aoki, taken under FWC MTP - 205

Satellite tags offer key insight into near real-time location data of leatherbacks, however they are cost-prohibitive (each tag costing over $3,500) and typically last only 7-9 months. Acoustic tags on the other hand typically cost around $500 and can last for years. They transmit an acoustic signal that is picked up by acoustic receivers placed in the ocean when the turtle passes within 800–1200 meters (2,600–3,900 feet) in clear conditions. The data is collected when the receiver is accessed and the data is uploaded to networks like the Ocean Tracking Network.

Derek describes the difference between working with satellite data and acoustic data saying, “Being able to watch our turtles’ location update every day with satellite data and get a glimpse of their diving behavior is an incredible sight to see. Working with acoustic telemetry is a little different, in that all our detections come in batches. These detections are much more accurate than satellite detections, so we are able to see very precise locations in relation to shipping channels, inlets, and other regions where interactions with humans could be high.”

Upwell tagged eight leatherbacks with acoustic tags in Pacuare National Reserve in Costa Rica in 2019, and these turtles were detected in the Caribbean and up the eastern seaboard for up to 2.5 years. During the 2021–2023 nesting seasons, Derek deployed five acoustic tags provided by Upwell and an additional 10 tags from collaborators. He has been analyzing the data from these new tags along with the Pacuare tags and his results have identified areas where leatherbacks could interact with human activity. Leatherbacks have been detected in The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s (BOEM) wind lease areas and high-use shipping channels as shown in the figure below, suggesting turtles are present within these areas during migrations and/or foraging seasons.

Acoustic detections of leatherbacks in the Gulf of Mexico and northwest Atlantic Ocean from 2019 –2023. Map insert (right) depicts detections of the South and Mid-Atlantic Bights overlayed with current and proposed Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) wind lease areas. Turtles with an ID of “P” were tagged in Pacuare, and an ID of “J” denotes turtles tagged in Juno Beach.

Derek says that seeing where the leatherbacks have been detected is always exciting, and that “The more acoustic detections we receive, the more excitement I have that acoustic telemetry can be a viable method to identify leatherback presence away from nesting beaches.” Derek hopes to deploy up to 20 additional acoustic transmitters during the next two nesting seasons, and that the data collected can help to identify gaps in receiver arrays at coastal foraging grounds. He also aims to increase knowledge about areas where leatherbacks are susceptible to human interactions, including participation in Upwell’s initiative to collaborate with fishermen to attach acoustic receivers to fishing gear (i.e., crab pots) to detect when and where leatherbacks are interacting with fisheries. Derek is presenting his current findings from this research at the 42nd annual International Sea Turtle Symposium.

“Derek’s research has done a great job of showing the utility of acoustic tracking as a tool for long-term data collection, and we hope to leverage this work to enhance our understanding about fine-scale movements of sea turtles and potential overlap with anthropogenic threats. The acoustic tracking data provides a useful fisheries-independent complement to satellite tracking and fisheries observer datasets”

This work is possible thanks to The Loggerhead Marinelife Center, Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Inwater Research Group, and Florida Atlantic University-Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute Foundation for funding this study. We extend additional thanks to FACT Network, ACT Network, and OTN members for collecting and distributing data detections. All images of nesting leatherbacks were taken by members of Loggerhead Marinelife Center under Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Marine Turtle Permit 205.