Brenna Eikenbary is an incoming veterinary student at Oregon State University with a Master’s in Global Health from Georgetown University. She focuses on One Health issues, including investigating the potential impact of harmful algal blooms on sea turtle health in partnership with Upwell.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), “Harmful algal blooms, or HABs, occur when colonies of algae — simple plants that live in the sea and freshwater — grow out of control and produce toxic or harmful effects on people, fish, shellfish, marine mammals and birds. While human illnesses caused by HABs are relatively rare, they can be severe or even fatal.”

HABs can also affect sea turtles and are fueled by a variety of environmental factors, including elevated ocean temperatures, nutrient pollution (such as nitrogen and phosphorus from agricultural/urban runoff and wastewater), increased sunlight, calm water conditions, and disruptions to the food web. Climate change and human activities are accelerating the frequency, duration, and intensity of these blooms.

HABs are an emerging One Health issue in our backyard impacting the health of humans, animals, and our shared environment. The economic and ecological impacts of HABs are profound. Coastal communities often face fishing closures and tourism losses in an effort to protect public health, while wildlife—including fish, birds, sea turtles and marine mammals—suffer the effects of biotoxin exposure. Among the toxins produced by HABs, domoic acid has been especially harmful, causing severe neurological and cardiac damage oftentimes leading to mass die-off events in marine mammals and seabirds.

Recent news coverage on a large-scale HAB event off the coast of southern CA

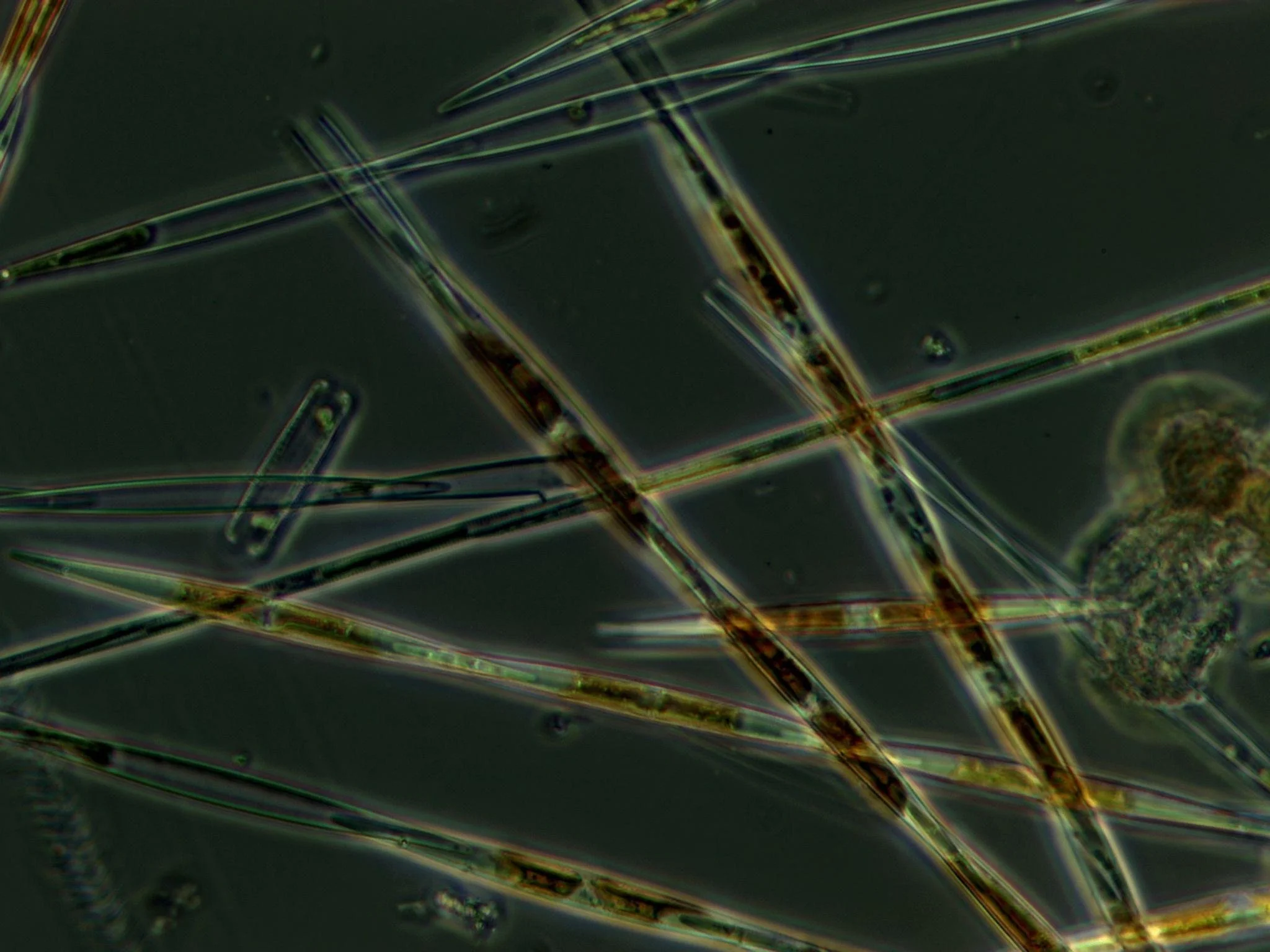

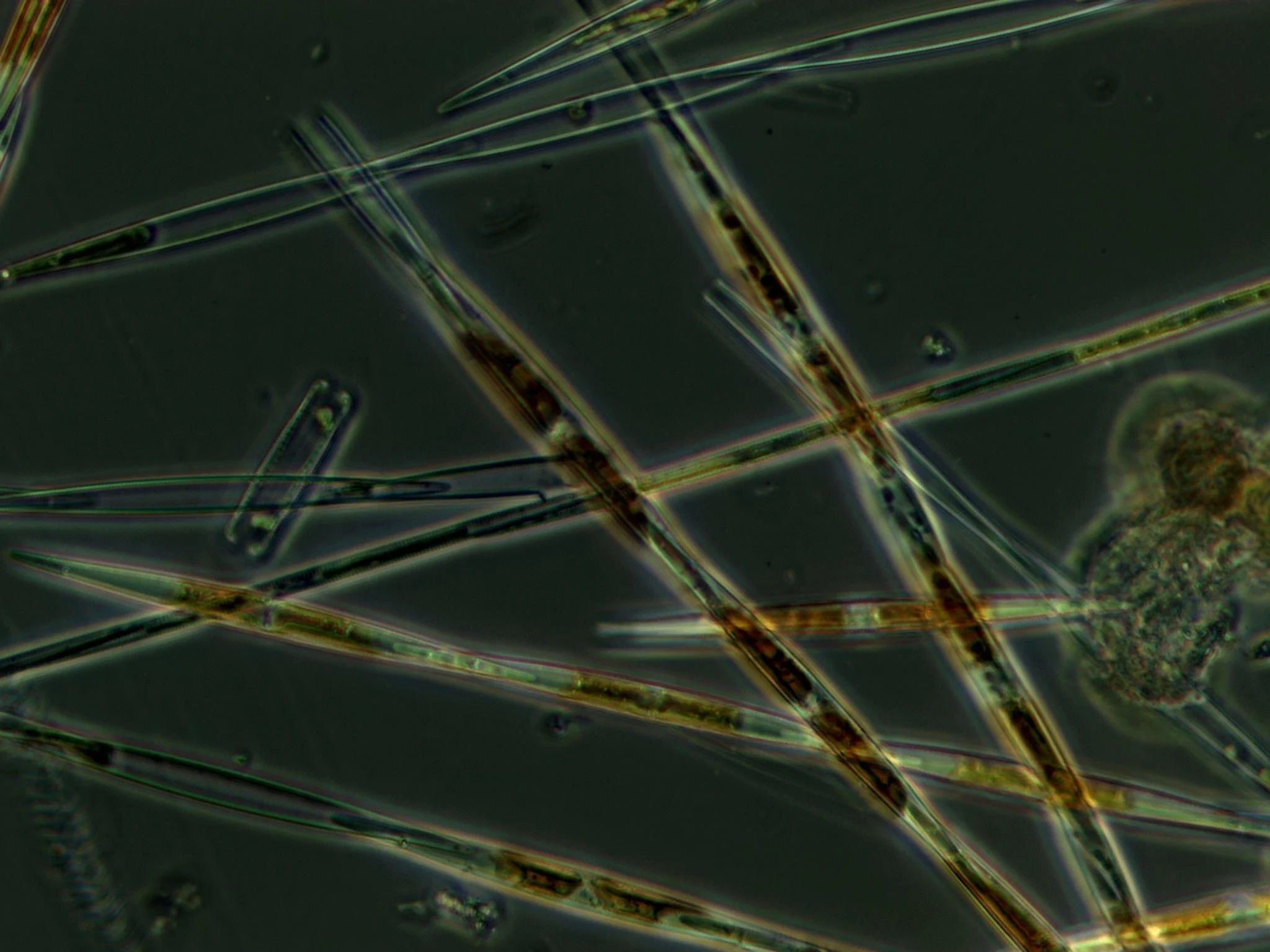

Cellular look at Pseudo-nitzschia, an algae that creates toxins like domoic acid when it blooms in large quantities. (From the NOAA Photo Library)

The U.S. West Coast has seen several significant HAB events in recent years. In Southern California, a bloom that began in March 2025 has led to the stranding and death of over a thousand marine mammals and seabirds, and is still ongoing. Similar events in 2015 and 2023 resulted in mass die-offs of sea lions and dolphins due to DA exposure, sparking concern among scientists and veterinarians about how HABs may be impacting other marine species—like sea turtles.

Investigating HAB Exposure in Sea Turtles

While the effects of HABs on marine mammals have been well documented, much less is known about their potential impact on sea turtles. Through my Cal Poly undergraduate senior project under the mentorship of Upwell Wildlife Veterinarian Dr. Heather Harris, I set out to investigate the likelihood of HAB exposure among sea turtles stranded along the West Coast since 1990. I became so invested in the project that I decided to continue working on it with Dr. Harris as I begin veterinary school at Oregon State University in the fall.

For this research, I compiled and analyzed data from multiple publicly available sources: the California Department of Public Health (CDPH), the California Harmful Algae Risk Mapping (C-HARM) model, the Coastal HAB Monitoring and Alert Program (HABMAP), and The Marine Mammal Center. These datasets allowed us to assess whether a bloom was likely present near the time and location of each stranding and to prioritize which tissue samples were most likely to yield meaningful results if tested for DA—especially important in the face of limited resources.

A stranded olive ridley turtle documented by Dr. Heather Harris

When laboratories and offices reopened after the COVID-19 pandemic, matching federal grants from NOAA and USFWS enabled us to test all of the stranded sea turtle samples (blood, urine, gastrointestinal contents) that had been collected by the West Coast Stranding Network for this purpose. c. With this comprehensive dataset in hand, we now have the first available data on biotoxin exposure in threatened and endangered West Coast sea turtles and an opportunity to explore how environmental conditions may be affecting their health.

Building Better Tools and Stronger Networks: The 2025 CalOOS Workshop

On May 9, 2025, Dr. Harris and I had the opportunity to participate in the California Ocean Observing System (CalOOS) Workshop in Avila Beach, hosted by the Central and Northern California Ocean Observing System (CeNCOOS) and the Southern California Coastal Ocean Observing System (SCCOOS). The workshop convened a diverse community of stakeholders—from researchers and aquaculture professionals to water board members, public safety, and education representatives—to share how ocean data is collected, accessed, and used to inform real-world decisions.

The workshop’s goals were clear: Share information about ocean data collection and availability, identify community information needs, improve delivery of existing data, strengthen coastal resilience efforts and explore partnerships to address data gaps.

CalOOS 2025 community workshop participants and facilitators. Dr. Heather Harris and Brenna Eikenbary are in the back row, fourth and fifth from the left, respectively. | Serena Lee

Participants learned about the technologies and monitoring sites that provide publicly accessible data on sea level, ocean sediment, temperature, tides, and HAB conditions. Some of these datasets span decades and serve as critical tools for understanding both immediate changes and long-term trends in ocean health. For researchers like me, the workshop was a unique opportunity to connect face-to-face with others working on similar challenges and explore ways to refine our approach to HAB-related data.

Next Steps in Our Research

Now that the sea turtle tissue and blood samples have been analyzed for domoic acid concentrations, our next step is to work with partner organizations that initially rescued or assessed these animals to collect intake forms, treatment records, and necropsy reports. By compiling these individual case reports, we hope to determine whether elevated DA levels correlate with specific physiological effects.

Brenna Eikenbary (left) and Dr. Heather Harris (center) evaluating a stranded sea turtle at The Marine Mammal Center in 2019

At the same time, we are investigating broader patterns: do DA levels vary by species, diet, geography, season, age, or sex? Answering these questions could help identify which populations are most vulnerable to HAB exposure and guide future conservation strategies.

To improve the reliability of our assessments, we’re integrating CeNCOOS/SCCOOS data and applying tools introduced during the CalOOS Workshop. We’re also collaborating with other HAB researchers we met through the event to refine how we define and track HAB exposure. These partnerships and datasets are helping us reduce uncertainty around bloom locations, growth phases, and potential overlap with sea turtle strandings—ultimately enhancing our understanding of the risks that HABs pose to marine life.

Final Thoughts

The CalOOS Workshop underscored the immense value of federally managed open-access ocean data and the importance of cross-disciplinary collaboration. As we continue our research into the impacts of harmful algal blooms on sea turtles, we are grateful for the tools, partnerships, and support that make this work possible. With HABs on the rise, strengthening our federal data infrastructure and our understanding of their ecological effects is more important than ever—for sea turtles, and for the health of people and our oceans as a whole.