At the turn of the millennium, the origin of leatherback turtles in California waters was unproven. Many assumed they originated from nesting beaches in Mexico or Costa Rica; few could have imagined the extent of their travels across the entire Pacific Ocean. We know now that West Pacific leatherbacks only make their epic trans-Pacific migration about every three to five years. Unfortunately, the batteries on early satellite tags didn’t last long enough to track their whole migration.

NOAA Scientist Scott Benson explains, “If 10 transmitters were deployed at a leatherback nesting beach in Indonesia, fewer than half might move toward the California foraging grounds that year and we’d be crossing our fingers that the transmitter and attachment would have the duration to make the 10-12 month journey. The number of tracks that arrived in California waters would’ve been so low that most folks might conclude that California waters are not very important to the population.”

It wasn't until Benson started monitoring for leatherbacks off California and deploying satellite tags on turtles foraging there that the scientific community and fisheries agencies began to recognize just how important US West Coast foraging grounds are to the West Pacific leatherback population. In September 2000, Scott Benson, with fellow turtle researchers Peter Dutton and Scott Eckert, captured and satellite tagged two leatherbacks swimming in Monterey Bay. Following their release, the turtles moved in a southwest direction. Both tags stopped transmitting before either turtle could complete remigration, but the data supported their working hypothesis that California’s leatherbacks originated from the western Pacific (and deployments in subsequent years continued to provide compelling evidence).

NOAA Scientist Scott Benson in Papua Barat (West Papua), Indonesia

Telemetry data from leatherbacks tagged in and around Monterey Bay in 2000 & 2001 indicated a connection to the western Pacific; however, there are multiple beaches and two nesting seasons (winter & summer), so researchers didn’t know which beaches would link to the US West Coast. To confirm that leatherbacks foraging off California were, in fact, the same turtles that nested in the West Pacific, Benson and Dutton initiated a multi-year satellite tracking program, which yielded some surprising results. The nine turtles they tagged at the nesting beach in the Kamiali Wildlife Management Area along the Huon Gulf coast of Papua New Guinea in 2001 moved into southern hemisphere waters near Australia and New Zealand. Benson repeated the effort with similar results in December 2003, when he returned to Papua New Guinea and tagged ten more leatherbacks at the same nesting beach. But West Pacific leatherbacks nest in two distinct seasons.

Working on a hunch that turtles nesting during the boreal summer might follow different migration paths, Benson deployed a new round of satellite tags on nine nesting leatherbacks at Jamursba-Medi in the Bird’s Head region of West Papua, Indonesia in July 2003. After nesting, some of these leatherbacks set off across the Pacific toward the North American continent–one completed the trans-Pacific journey to foraging grounds off northern Oregon.

The telemetry results made waves in the scientific community, confirming one of the longest known animal migrations on the planet. It also meant that successful conservation of the West Pacific leatherback population would require transboundary coordination to ensure protections for this highly migratory species across its entire range and life history cycle.

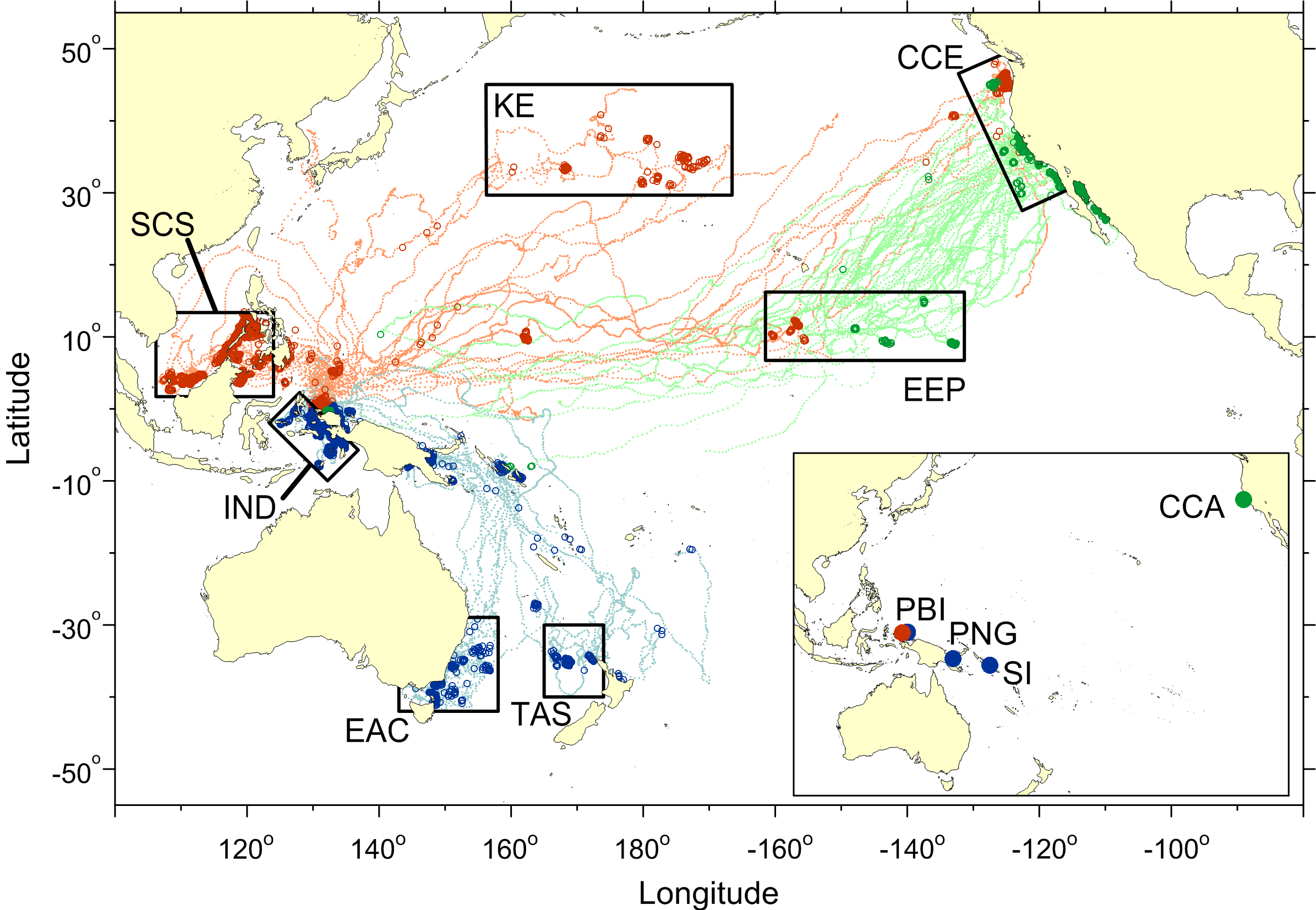

Mapped satellite tracks from tags deployed on 126 leatherbacks (Benson et al. 2011)

From 2000 to 2007, Scott Benson and colleagues deployed a total of 126 satellite tags on West Pacific leatherbacks at both nesting and foraging sites. They also collected measurements on each turtle’s body condition. The results revealed distinct migratory patterns and foraging strategies associated with different seasonal nesting patterns. Moreover, Benson’s work clearly demonstrates the importance of distant temperate foraging grounds off the US West Coast to leatherbacks nesting in the West Pacific.

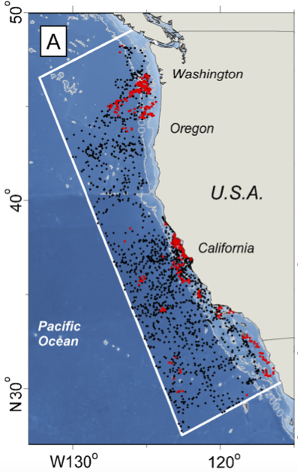

Mapped satellite telemetry data indicating foraging (red) and transit (black) behaviors in the California Current Ecosystem with 200-meter and 2000-meter isobaths (Benson et al. 2011)

Rich in gelatinous prey, the California Current enables leatherbacks to improve body condition and store energy for long-distance remigration and nesting. Benson’s research also indicates that leatherbacks exhibit strong foraging site fidelity in the California Current, further underscoring the importance of providing protections to leatherbacks in these important foraging habitats they consistently return to and rely upon to build energy reserves between nesting cycles. These scientific discoveries on the value of foraging zones off California, Oregon and Washington to West Pacific leatherbacks encouraged the US federal government to officially designate them as Critical Habitat for this critically endangered species in 2012. (Critical habitat is defined as an area needed to support recovery of a species listed under the Endangered Species Act.)

To learn more about Scott Benson’s groundbreaking scientific research, read Benson et al. (2011) Large‐scale movements and high‐use areas of western Pacific leatherback turtles, Dermochelys coriacea published in Ecosphere.

Check out our upcoming related blog post on Upwell’s continuing work with Scott Benson and NOAA to monitor and protect West Pacific leatherbacks in the California Current.