Observing juvenile sea turtles at sea is challenging due to their small sizes (which make biologging difficult), as well as their enigmatic behaviors like diving, and the vastness of the ocean in which they roam. The early phases of sea turtle life history, commonly known as the “Lost Years,” are poorly understood despite significant advances in animal and ocean observation technologies. Upwell began the Lost Year’s Initiative to explore the promise of new tag miniaturization technologies and their potential to shed light on the lost years period, which encompasses the time at which hatchlings enter the ocean until they return as mating and nesting adults.

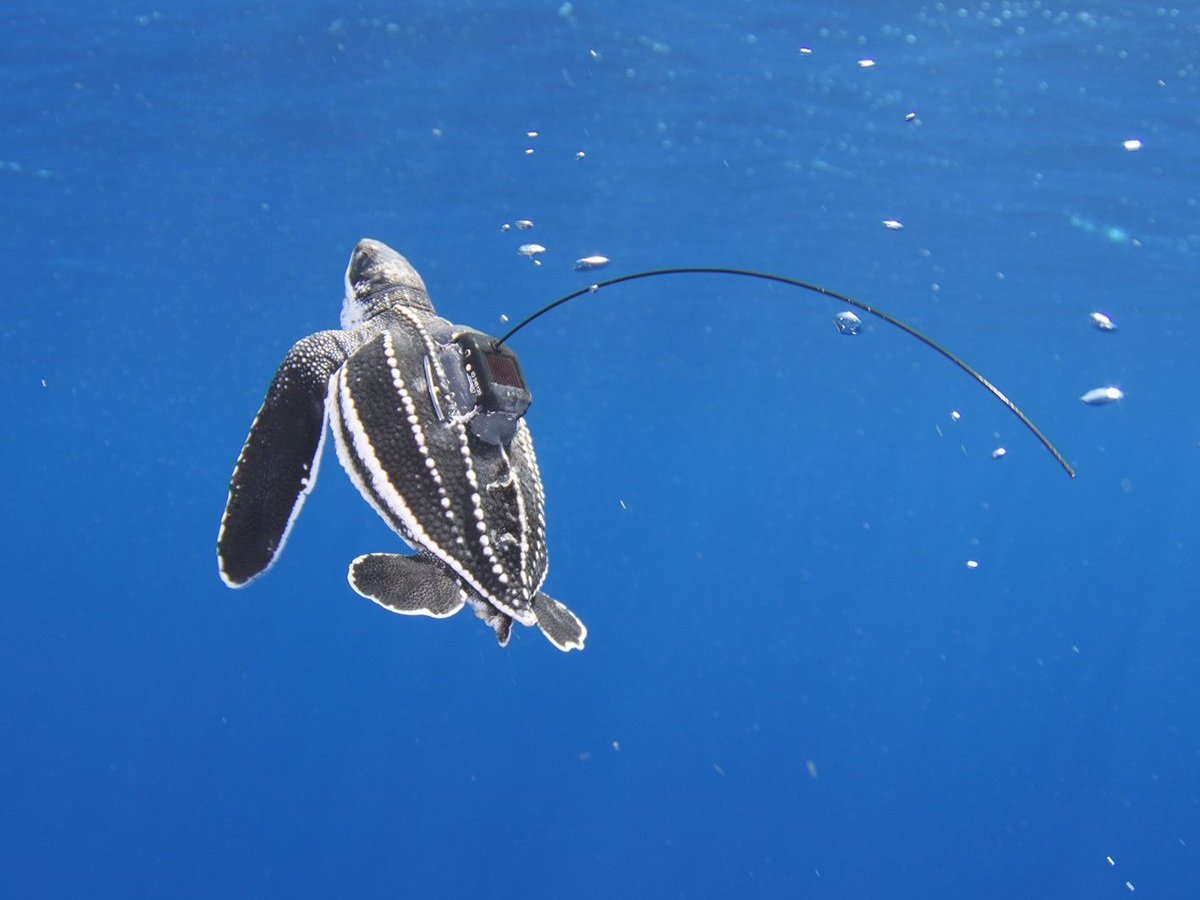

With a team of collaborators, we tested new specially-designed prototypes of Lotek microsatellite tags on 160 juvenile sea turtles of four species in the North Atlantic. The data from these tags was analyzed by Tony Candela, Oceanographer and Marine Ecosystem Modeler for Upwell, Mercator Ocean International and for the Centre d'Etude et de Soin des Tortues Marines (CESTM) of the Aquarium of La Rochelle. Tony’s analysis was published in a new article, "Novel Microsatellite Tags Hold Promise for Illuminating the Lost Years in Four Sea Turtle Species."

We sat down with Tony to talk about this article, his process as lead-author, and the important implications of these findings for the bio-logging community.

Q: How did you first become interested in the topic of sea turtle dispersal and movements?

A: For years I studied ocean currents, the movement of water masses with different temperatures, salinities and so on. However, I have always aspired to play a direct role in marine conservation and was looking for ways to leverage my knowledge of ocean physics to contribute. Through my research and discussions with Dr. Philippe Gaspar and Dr. George Shillinger, I learned about the lack of information about the early life stages of sea turtles and how that gap in knowledge creates significant challenges for their conservation. Since juvenile turtle movements are largely influenced by ocean physics, for example the ocean currents that shape their dispersal, working to fill in that gap was the perfect way to align my background with my values.

Q: What brought you to work on the data analysis of Upwell’s Lost Years Initiative?

A: I had already been working with Upwell on the creation of numerical models, like the Sea Turtle Active Movement Model (STAMM), which provides theoretical yet significantly useful information about how juvenile turtles might disperse in the ocean. But models alone are of limited value without a minimum of observational data to validate the simulated results. Upwell’s Lost Years Initiative has made significant advances in tag miniaturization and novel attachment methods, enabling the collection of the data needed to validate our models. George approached me about analyzing the data collected from these tags so far, which resulted in our recent publication. I am also completing a PhD on the application of satellite tracking and numerical modeling to unveil the initial dispersal of juvenile sea turtles using the data from the tags.

Q: What was your process for analyzing this data?

A: Once the turtles are equipped with microsatellite tags and released into the ocean, my task is to retrieve the data sent by the tags and document the evolution of their oceanic journeys. One part of my work is focused on providing an analysis of the turtles’ movements. I look at their location data paired with real-time environmental data like ocean currents or the surrounding water temperature to try to understand the reasons for these movements. I send this analysis in a weekly update to our international team of collaborators until all tags cease transmitting.

The other part of my work is focused on documenting the performance of the tags by analyzing the battery status, transmission power, or the number of received transmissions, among others. When a tag stops functioning, I document its operating time and try to understand the reason for its failure with the limited data we receive. Is the battery depleted? Has the tag been bio-fouled (for example by algae growth) or damaged? Or has it detached due to the turtle's relatively fast carapace growth, especially among very young turtles? There are many questions to investigate.

Q: What surprised you most about your findings?

A: I think the most surprising thing for me is the incredible diving behavior of very young leatherback turtles. It turns out that very young leatherback turtles measuring between 7 and 10 cm long, dive daily to depths greater than 20m! It is interesting to note that the tags attached to turtles of this species recorded the shortest tracking durations. It would not be surprising to see a cause-and-effect relationship between the intensive diving behavior of very young leatherback turtles and the short tracking durations of their tags. This is one of the many things we learned from this study, and is supported by more recent observations of leatherback turtles of the same size reaching much greater depths: up to 100m!

Q: What were the most challenging aspects of this work?

A: The most challenging aspect of this work was its interdisciplinary nature. I have a background in ocean physics, but for this study, I had to understand and analyze data and concepts from very different fields of expertise, ranging from animal biology to satellite telemetry, electronics and complex system engineering. It was a significant learning curve for me to be able to analyze all aspects of the performance of these tags and engage in discussions with all the different experts involved in this study. I would like to take this opportunity to thank them all because I learned so much through the discussions I had with them.

Q: You worked with many of Upwell’s partners around the Atlantic to complete this manuscript. Can you describe this process? Why was this collaboration important?

A: It was incredibly rewarding to see all these researchers and individuals from different fields of expertise and different countries coming together to work towards the same goal: improving our capability to track these young turtles.

It was indeed a real challenge for me to work with people from various fields of expertise and countries. However, this collaboration went extremely well, facilitated by regular email exchanges and video conferences to share our analyses, questions, and thoughts on the subject, thus pooling our diverse expertise.

Such interdisciplinary collaboration is crucial for studying a problem in its globality and gaining insights from various perspectives. The diversity of countries involved in the study is also essential for researching highly migratory species of sea turtles that traverse the jurisdictions of multiple nations. To be effective, the effort must be global.

Read the full article, "Novel Microsatellite Tags Hold Promise for Illuminating the Lost Years in Four Sea Turtle Species," published in Animals, and learn more about Upwells’ efforts to understand juvenile turtle’s lives at sea through our Lost Year’s Initiative.