Hawksbill sea turtles may be best known for their ties to coastal reefs, but these remarkable animals are far from homebodies. They’ve been recorded embarking on impressive migrations—sometimes traveling anywhere from 73 to over 1,000 kilometers in just a few weeks. In the Caribbean, where hawksbill numbers have plummeted by more than 90% in the past 80 years, tracking these journeys has become more important than ever. By understanding where they go, how long they stay, and which habitats they depend on, we can better protect the broader areas that are vital to their survival.

Much of the current telemetry data collected by tagging hawksbills is from adult females, due to the fact that they are easiest to tag when they crawl up the beaches to nest. To expand our knowledge of small juvenile hawksbill movements, Upwell teamed up with ProTECTOR, Inc., an organization with the goal of advancing our understanding of sea turtle biology and ecology through research throughout the coasts of Honduras. After more than a year of discussion and planning, Upwell’s Executive Director Dr. George Shillinger reached out to ProTECTOR, Inc. Founder and President, Dr. Stephen Dunbar for ProTECTOR, Inc. to join the Lost Years Initiative, Upwell’s effort to better understand juvenile turtles’ movements and habitat use.

From left to right: Mr. Paolo Garcia, Dr. George Shillinger, Dr. Stephen Dunbar

Dr. Dunbar commented on the collaboration, saying, “For ProTECTOR, Inc. this was a golden opportunity to partner with Upwell to really expand our understanding of early-stage movements of hawksbills hatching in the Bay Islands. The tracks of these small turtles strongly emphasizes the links between several countries through their coastal waters, and the need for transnational conservation policies that protect these turtles during these very vulnerable life stages.”

ProTECTOR, Inc. helps oversee a program in collaboration with environmental managers on one of the Bay Islands where hawksbill sea turtles nest. Thanks to this local partnership, some of the hatchlings are typically held until ProTECTOR, Inc. can flipper tag them in advance of their release to the wild. Flipper tags enable researchers that re-capture turtles to look up the tag numbers in a database and find out where else the turtle has been caught. Now, in collaboration with Upwell, some of the turtles would also get a Lotek micro-satellite tag to provide near real-time data on their location and diving behavior.

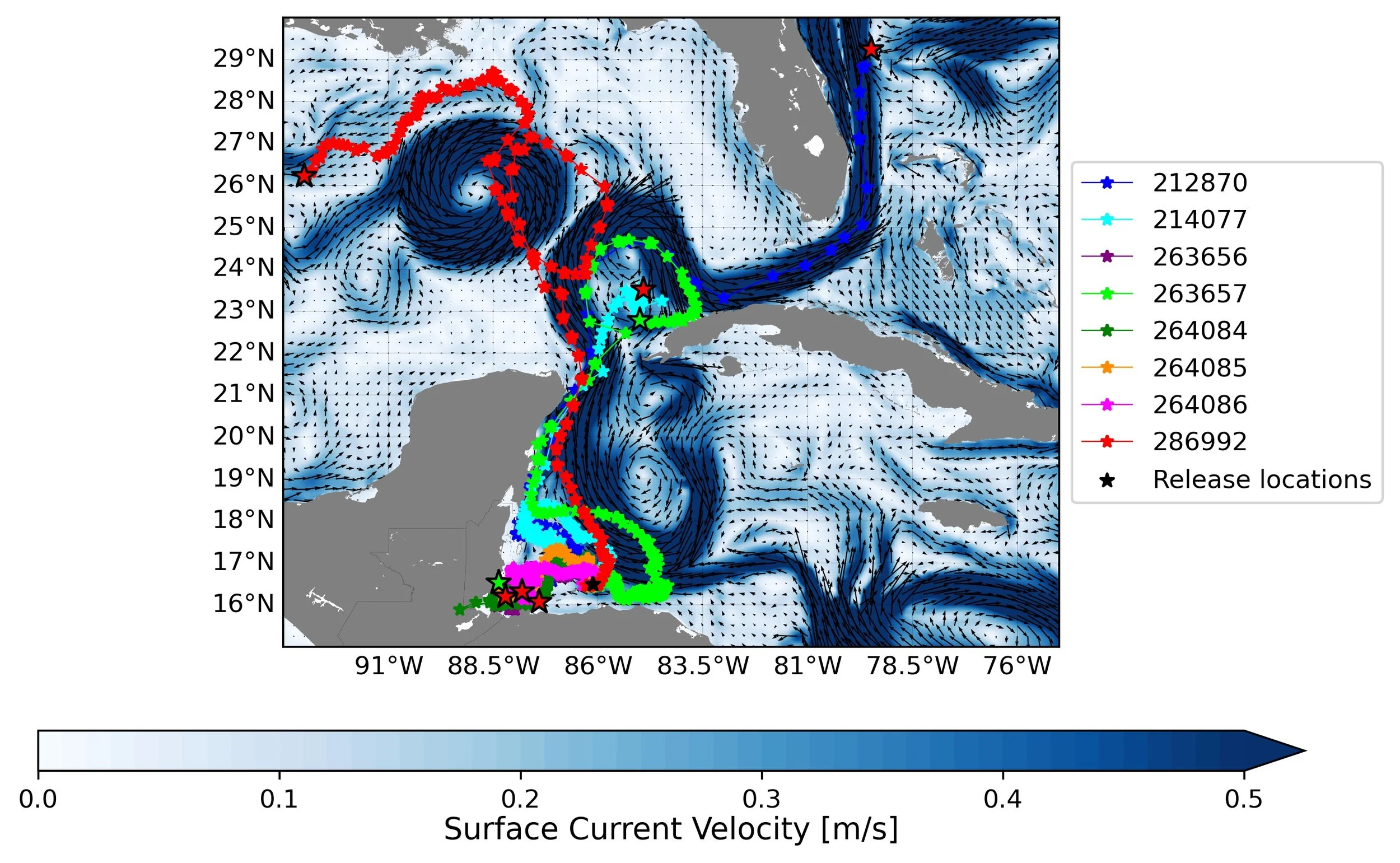

In early July, Dr. Shillinger traveled to Roatan, Honduras, where the collaborative team worked together to tag eight juvenile captive-reared hawksbills with micro-satellite tags. The turtles were then released just off of the northeast reef of the Bay Islands. While the dive behavior transmitted by the tags seems to be pretty uniform, with all turtles generally staying in the first 5 meters of the water column, their journeys are quite different.

Two turtles took off in the current heading north and then parted ways. Turtle 992 swam into the Loop Current in the Gulf of Mexico, making a full loop before heading west! The Loop Current is a swift moving current that can vary in size throughout the year, but it generally enters the Gulf of Mexico before looping back around and heading towards the Atlantic through the Florida Strait. Meanwhile, Turtle 870 is now heading up the Gulf Stream to the east of Florida, seemingly followed by turtles 657 and 077. Two other turtles remained closer to the release location, associating with neritic reef habitats off the coast of Honduras and Belize for the past 8 weeks.

Upwell Executive Director, Dr. George Shillinger remarked, “The provision of movement and behavioral data from very early-stage hawksbill turtles presents an opportunity to address significant data gaps regarding dispersal and habitat use of young turtles within the MesoAmerican Barrier Reef Region and the Gulf of Mexico, extending to the southeastern US seaboard. In addition to enhancing our learnings about the life history of hawksbills turtles, these data can also be applied towards conservation and management strategies that aim to protect and recover this critically endangered sea turtle population.”

At 70 days since release, two of the eight tags are still transmitting. The end of transmission doesn’t necessarily mean the end of the turtle, and there are numerous possibilities as to why a tag may go offline. The tags are designed to shed as the turtle’s carapace grows. Hawksbills are also known to spend their time in reefs where they are more likely to bump against rocks and coral that could disengage the tag's attachment, and where predation by sharks or large fishes is also a possibility.

Although these eight turtles and the data they have transmitted are just the beginning, it is incredibly exciting to have a window into this understudied life stage and see the diversity of their travels. Despite international trade bans on the sale of turtle shell products and great protections on nesting beaches, the hawksbill remains listed as Critically Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. We hope that collecting movement data from juvenile hawksbills can help us paint a more complete picture of their habitat use - a picture that we can then use to inform targeted conservation strategies.