One of the biggest challenges in protecting sea turtles is that they are constantly on the move. All sea turtle species make migrations (big or small) from their nesting grounds to foraging areas. The protection of migratory species like sea turtles requires coordinated conservation efforts between all territories that they cross through. For example, the USA, Canada, Mexico, Japan, and Russia participate in the Migratory Bird Treaty Act to protect the bird species that travel regularly across their borders. But what happens when the area that needs protecting doesn’t belong to any country?

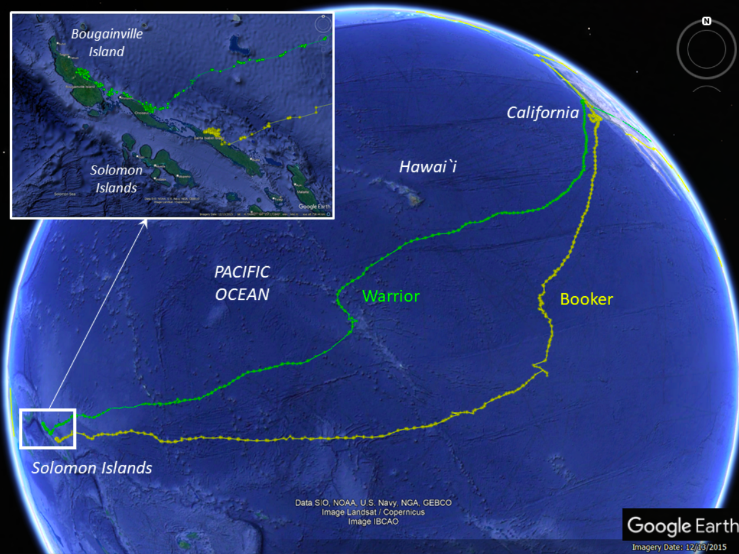

The transoceanic migrations of Booker and Warrior, two leatherbacks tagged off the California Coast by the Upwell and NOAA collaborative team. Their migrations crossed through the EEZs of multiple countries as well Biodiversity Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, also referred to as high seas.

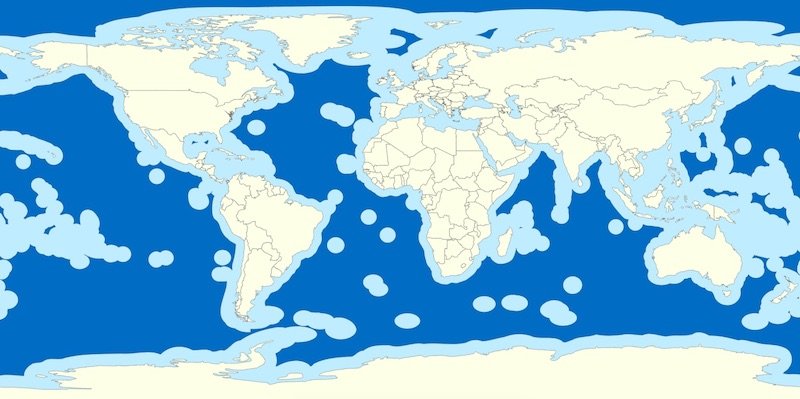

It is estimated that nearly two-thirds of the ocean is considered “high seas,” or Biodiversity Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) that belong to no nation. While various governing bodies exist (for example, the International Sea Floor Association), management efforts are fragmented and insufficient to handle the growing pressure to exploit the resources in these areas through fishing, mining, and other methods.

A map showing Exclusive Economic Zones of the ocean in light blue, and Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction in dark blue from the Wikimedia Commons.

In June 2023, after nearly two decades of negotiations, UN member states adopted a legally binding marine biodiversity agreement, providing a coherent and holistic framework for protecting the high seas, known as the BBNJ treaty. This treaty encompasses various themes from sustainable fishing to equitable sharing of scientific research (including discoveries of biological or genetic resources), to the establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). The treaty’s contents are both in need of further definition and highly debated, with some arguing it will do too little while others argue too much. The stakes are high and the stakeholders are many, including sea turtles and other migratory marine species.

To support the protection of migratory marine species, researchers from Upwell and MigraMar (a network of scientists that study migratory species in the Eastern Pacific, of which Upwell ED Dr. George Shillinger is a member) put their wildlife telemetry data into action by contributing it to the recent publication, “Global Tracking of Marine Megafauna Space Use Reveals How to Achieve Conservation Targets." This article amassed worldwide marine animal tagging data to provide a strategy for the effective conservation of marine megafauna. The study concluded that the popular 30X30 goal of protecting 30% of the ocean by 2030 will be insufficient for effective conservation of many species and leave important areas vulnerable to major human-created threats.

Since sea turtles cannot voice their opinions for inclusion in the treaty, Dr. George Shillinger and Dr. Erick Ross Salazar, Executive Director of MigraMar, joined a delegation of MigraMar colleagues to vocalize the urgent need to protect migratory marine species at the third UN Oceans Conference in Nice, France. At the conference, the delegation advocated for including protections and conservation efforts for sea turtles and other migratory species in the framework of the treaty. Dr. Ross Salazar stated, “Reaching the 30 by 30 target is very important; however, we need to be more ambitious if we truly want effective conservation of migratory species. Protected areas must be the backbone of conservation strategies, but we must also plan how that remaining 70% will be managed and how we can reduce negative interactions between human activities and migratory species.”

MigraMar members and staff at the UN Oceans Conference in Nice, France, from left to right (back row) and right to left (front row): Erick Ross Salazar-MigraMar, Todd Steiner-Turtle Island Restoration Network, Frida Lara-Orgcas, Sandra Bessudo-Fundación Malpelo y Otros Ecosistemas Marinos, Randall Arauz-CREMA, George Shillinger-Upwell Turtles, César Peñaherrera-MigraMar, Marta Cambra-MigraMar, María Virginia Gabela-MigraMar, Jair Urriola-CMAR.

Although 115 nations initially signed the treaty in 2023, 60 must ratify it by September 20th, 2025, for it to enter into force. After an initial push after the treaty’s creation, the number of ratifications was few and far between until this year’s UN Ocean conference in June, when 18 more countries ratified. However, at the time of writing this blog, the treaty is still short of meeting the ratification goal.

So, will the ratification of the BBNJ treaty save sea turtles?

Not necessarily. While certain actions that could result from the treaty, like bycatch reduction or establishment of MPAs in the high seas, have the potential to reduce threats that turtles face at sea, there is currently no clear pathway for putting the contents of the treaty into action. Its ratification will likely be followed by the creation of governing bodies and financial systems to further detail how the treaty’s contents will be carried out.

Dr. George Shillinger remarked, “Upwell’s work protecting turtles in their at-sea habitats requires that we develop political pathways, such as those promulgated within the BBNJ Treaty, that foster international collaboration and commitment to protect turtles across the extent of their ranges. While the process of forging these agreements is difficult, conservation of highly migratory species is not possible without global, transboundary strategies, so we will continue to support efforts to foment international collaboration however we can.”

What if ratification fails?

It could mean a longer road to the creation of an international agreement. Collaborative frameworks can play a large role in facilitating conservation efforts and have been key to the protection of various migratory and marine species in the past. For example, the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling largely stopped commercial whaling in countries around the world and helped curb the decline of whale populations, and even allowed many species to rebound.

Most sea turtle species spend large portions of their life history in areas considered high seas, with leatherbacks standing out as the greatest world travelers. In the 2018 article “The political biogeography of migratory marine predators” by Autumn-Lynn Harrison et al., leatherbacks in the Pacific Ocean crossed through the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of 32 countries and the high seas. Upwell and MigraMar will continue to push for coordinated and collaborative protection efforts, whether it be through the BBNJ Treaty or by forging other international collaborations.

Sources not linked in text:

https://apnews.com/article/high-seas-treaty-oceans-un-ocean-conference-53ad46ae3cf8737ec82d925761a3d089