In 2022, the collaborative Upwell and NOAA leatherback monitoring team tagged three leatherbacks between July and September. Then, in 2023 and 2024, although the team observed habitat with abundant sea jellies and ocean sunfish (a proxy species for leatherbacks), and had one near miss in the Gulf of the Farallons, they were unable to tag any turtles. This is not unusual because leatherbacks show interannual variability in their migrations, which means that the turtles that nest in the West Pacific during the summer do not always travel to the US West Coast to forage and will go to other areas in the North Pacific instead. In addition to this variability, the population has severely declined, having lost 80% over the last four decades.

Photo by Heather Harris

On a survey in late September this year, the crew of the Sheila B. received the alert from their aerial counterparts via radio that a leatherback had been spotted. The aerial team carefully guided the vessel team to the turtle, and they were able to capture it and bring it on board for a health assessment and to deploy satellite and acoustic tags. The male leatherback weighed a whopping 438 kg (almost 1,000 pounds).

Photos by Captain John Douglas

The team always names tagged leatherbacks in order to easily manage their data, and this leatherback was named "Ricky Ricardo" in honor of the late Dr. Ricardo Tapilatu whose lifelong research contributions are fundamental to West Pacific leatherback conservation efforts. Dr. Tapilatu spent decades mentoring marine science college students at the State University of Papua (UNIPA) and engaged in efforts to protect the West Pacific leatherback, helping to document the long-term decline of this species and monitor its main nesting beaches in Papua Barat, Indonesia. His research continues to inform much of our conservation efforts today.

Once Ricky the leatherback was released back in the ocean and disappeared swiftly under the waves, the team enjoyed a celebratory dinner at the local taqueria, a longtime tradition after tagging the first turtle of the season. However, for Upwell Wildlife Veterinarian Dr. Heather Harris, there is more work to do once back on shore. Blood samples were processed in a makeshift hotel laboratory and will be analysed for clinical health parameters and biotoxin exposure.

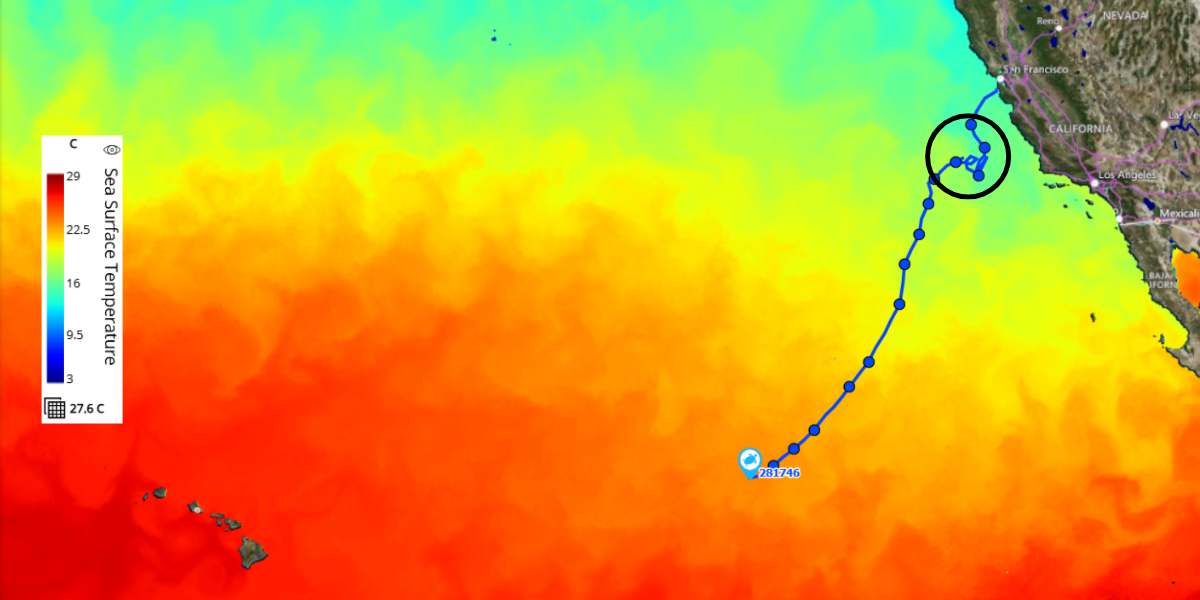

After more than 85 days days, Ricky’s tag is still transmitting. At first, he swam farther offshore before meandering in what appears to be feeding behavior (encircled in black in the image below). When we see that a satellite track is doubling back and/or moving in circles, we believe it corresponds with feeding behavior because a leatherback that finds a large patch of sea jellies will swim through it multiple times as it consumes enormous amounts. Think of it as someone eating at a buffet who makes multiple trips from their table to various food stations to fill their plate.

After spending time feeding, Ricky swam in a direct path farther out to sea, most likely beginning his migration back across the Pacific. Although the satellite tag will likely only capture data from this season, Ricky also has an acoustic tag that can transmit for up to ten years. Acoustic tags transmit an acoustic signal at a frequency that does not interfere with leatherback hearing, but does get picked up by acoustic receivers placed in the ocean, usually in coastal areas. Researchers can then retrieve the data from the receivers to know if a tagged leatherback has passed by.

While the aforementioned interannual variability and overall declining leatherback population make it hard to predict, we hope to see Ricky again someday. In the meantime, Upwell and NOAA will use the data from his satellite tag, along with all the other data collected through our aerial and vessel surveys, to help inform management decisions that can protect leatherbacks in US waters.